It is my strongly held belief that no one should wake before the sun rises, and yet here I am struggling to open the shutters of the coffee shop at 6:30am when the day is still dark and cold, mumbling to myself something about the sun not having risen. I’ve already been awake for two hours, commuted for 30 minutes and spent another 30 turning on the machines, receiving deliveries and doing the health and safety checks. I am exhausted, and as soon as I get back into the tiny, cold shop, the first two customers are lined up at the till. My colleague is late, and I already know it is going to be a long morning.

It is my strongly held belief that no one should wake before the sun rises, and yet here I am struggling to open the shutters of the coffee shop at 6:30am when the day is still dark and cold, mumbling to myself something about the sun not having risen. I’ve already been awake for two hours, commuted for 30 minutes and spent another 30 turning on the machines, receiving deliveries and doing the health and safety checks. I am exhausted, and as soon as I get back into the tiny, cold shop, the first two customers are lined up at the till. My colleague is late, and I already know it is going to be a long morning.

It begins easily enough: two small lattes. The customers both pay on card and move around to the side. I click a double coffee shot into the portafilter and pack it down – not too tightly – and screw it into the machine. I press the double espresso button and put two small takeaway cups under the stream of golden and black coffee. Then I take one of the six four-pint bottles of pre-opened milk by my feet and pour what I know is the perfect amount into the metal jug, put the steamer in the milk and pull the lever. I move the jug down until the steamer is near the top of the milk and let it foam and stretch the milk out ever so slightly. Then, as the coffee stops dribbling and the milk reaches temperature, I turn the lever off and pour the milk into the cups with a touch of foam at the top and hand them over. There is no new customer yet so after my colleague, who is hungover, finally arrives, I cram the croissant I put aside earlier into my mouth and start to make myself an espresso. Soon, I’ll have no time at all. This is the quietest it will be until my shift finishes.

Working as a barista is not an easy job. Those who work in fancier coffee shops can take all the time in the world to make a coffee and serve it alongside a £5 croissant. Then there are those who serve hundreds of tired, caffeine-starved and irate commuters as quickly and as well as possible between the hours of 6:30 and 9:00am. I worked in one of the latter, at a kiosk on a platform of a train station.

Fortunately for me, I had a good boss who cared deeply about quality, nice colleagues, and the pay got me through my MA degree. Above all, I was able to learn a lot about people and coffee.

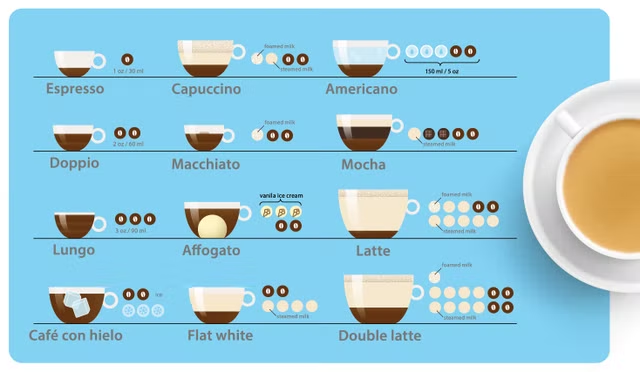

The first thing I realised is that, despite people in the UK consuming 98 million cups of coffee a day, most seem to know nothing about the coffees they are ordering. For example, few know the difference between a cappuccino, a latte and a flat white, and so have no idea if they’re served the right drink.

Let me explain. A cappuccino is much the same as a latte except that it is more foam than steamed milk, while a latte should be mostly steamed milk with a bit of foam at the top. A flat white, meanwhile, is highly specific. The milk should be somewhat similar to that of a latte (although with less foam), but it is a smaller, 160ml drink with two shots of espresso. If a barista hands you anything other than around a 160ml drink, it’s a sign they don’t know what they’re doing – avoid them.

Which brings me to alternative milks. There are only two that steam well: oat and soya. Almond and coconut should be avoided. They scorch easily and are usually disgusting with coffee. And here is a big tip: never ask for an extra hot oat or soya (or almond or coconut, if you insist). It’s simply impossible. If anything, those drinks should be served a little cooler than regular milk for them to be delicious. This is the reason big chains – and those that don’t know what they’re doing – are often atrocious at alternative milks. They treat them like regular milk and scorch the crap out of them, leaving them tasting awful. You’re already paying more for the milk, so you might as well get a delicious coffee. Independents are usually much better at this.

At 7:30am we’ve already served 30 coffees and made five toasties. I’ve been on the milk steamer all morning and burnt my hand twice. My colleague takes the orders and prepares the coffee shots and talks absentmindedly to the attractive customers while ignoring the others – yes, if the barista fancies you there’s a chance they’ll give you a coffee for free and, yes, you will be referred to behind your back as your drink order (I fell for Oat Milk Hot Chocolate, who graced the shop with her presence only sporadically).

The orders are lining up and there’s a minute until the next train arrives. There are five people waiting for drinks. I get the coffees done and as I hand over the last one the man snatches it, spills a bit on himself, and runs for the train as the doors are closing. He makes it. Not a word of thanks. I look up the platform and see her coming toward us. She walks with the aura of someone who, should anyone bump into her, would throw away the item of clothing they’d touched. I already know her order. I saw her yesterday and the day before that and every other weekday morning before that. She reaches the till and, simultaneously looking down her nose and rolling her eyes at us, orders her terrible coffee: “An extra hot, extra shot, decaf almond milk latte.” Fine, I happily take her money – extra for the shot, extra for the milk – and hand her over a steaming, scolded mess in a cup. After all, the customer is always right… except when they’re not.

There are two things wrong here. Firstly, her attitude. It’s hard not to notice the people looking down on you, who think you’re less than them because you haven’t amounted to anything but a “lowly” barista. The way customers talk to you when (they think) a mistake has been made is as if you are a slug and not a human being who has been awake since 4:30am and served over 100 drinks already – most of which are perfect and tasty, by the way. Being nice to your barista costs nothing. Many of us are using it as a stepping-stone to other careers and studies, while others I know simply love the job – they could tell you as much about the fragrances of an Ecuadorean coffee as a sommelier could about a 1976 Beaujolais.